The Irish Piebald & Skewbald Studbook

IPSA

Irelands dedicated coloured horse studbook, for coloured horses of all types, with or without pedigree recorded.

Geographical areas covered: Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland & EU

*Click here to request a DNA Kit (online order form)*

Definition:

Horses come in all shapes, sizes and types, with one major distinction – Colour.

Here in Ireland we use the terms Piebald or Skewbald to describe certain horse colouration.

In other countries you will see references to Coloured or Paint horses which in many cases these descriptions really have the same meaning.

A Skewbald and Piebald is defined by its external visible coat colouration and markings and not by its genetic makeup or type. They are therefore distinctive and unique from other “coloured”, splash marked, or extended leg marked breeds or types.

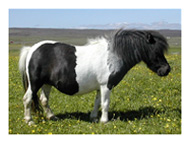

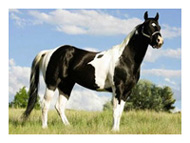

PIEBALD Large irregular patches of black and white (usually black on a white base)

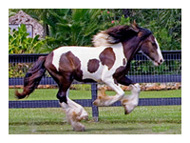

SKEWBALD Any other colour or colours and white i.e., bay, brown, chestnut, grey, dun or palomino and white. There may be some black marks in addition.

If a horse or pony has white markings on the head, legs, belly and / or mane or tail in isolation,

it cannot be considered as a Piebald or Skewbald.

Clyde markings do not constitute a Skewbald or Piebald in isolation from other colour.

Pinto\Paint is an American term which generally means either Piebald or Skewbald; however there is

also a technical difference in that they have different meanings. The Pinto Horse Association is a colour

registry, and Pintos can be any breed. Paints are APHA-registered horses that can prove parentage from

one of the three approved registries AQHA, TB and APHA, as well as meet a minimum colour

requirement. While a loud-coloured horse could be double-registered if it met the breed standards

specified by each registry, the two registries are independent.

Some History:

The popularity of the coloured horse in America has played a big part in their revival in Europe.

When Columbus (re) discovered the New World, there were no horses there. This is strange, for horses were abundant in North and South America over ten thousand years ago. Why these animals became extinct in still a puzzling question.

Like all other horses, Paint or Coloured Horses arrived in America in two general ways. The first, and most significant, was by way of the Spanish conquistadors. The second was through importations from England. The first recorded arrival of the coloured horse to the new world was made in 1519 with Hernando Cortes – the Spanish explorer who conquered Mexico.

As settlement spread to North America the Indians (by trading and borrowing them!) adapted themselves easily to the horse. Because they had an eye for anything bright or colourful, the Indians sought out the painted horse. To them the horse was more than a war horse or a means of travel. He was a medium of exchange and a status symbol.

The Paint Horse has always been associated with the Indian in legends, stories and songs. At the siege of the Alamo, at the Fetterman massacre, at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Paint Horse was there.

The cowboys applied such names as piebald, skewbald, calico, overo, spotted, pinto and old paint. Those who rode one, owned one, or worked one knew that most Paint Horses possessed action as quick as any horse of their time. They were willing to give credit where credit was due.

By 1700 the sport of horse racing was well established and had spread throughout Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. In the beginning races for distances up to a quarter-mile (origin of the “quarter

horse”) were popular among the plantation owners and backwoods settlers. But as thoroughbred horses entered the American scene, longer courses were laid out in major racing centers for racing pedigreed horses and the importation of Coloured horses diminished.

By the nineteenth and early twentieth century’s vast herds of wild horses roamed the western deserts and plains. Although the wild horses of America were not of the unrestrainable character as the truly wild horses of Europe and Asia, they ranged freely in great numbers and could be claimed by anyone willing to attempt their capture.

By this time the Paint Horse could have suffered a serious decline in western America similar to that of the mustang, had it not been for a new form of entertainment involving horses that began in 1883– the wild-West shows. These shows were designed to present to the American people the highlights and excitement of western life. The Paint Horse added a touch of brilliance to these colourful affairs.

When the shows faded in the 1920’s, one of the most spirited of American sports, the rodeo, came into national prominence and the popularity of the coloured horse was reaffirmed.

Here in Ireland:

The traditional coloured horse of Ireland and Britain is probably the Vanner and its smaller version, the coloured cob (or Tinker, as the Germans call it). These were the original Traveler’s (Gypsy) horses.

In Ireland in the late 1960’s early 70’s the biggest collection of these horses were used to pull Gypsy caravans earning their living pulling tourists around the country side. These heavier types have for years been crossed to Thoroughbred mares. The best have the substance of a good middleweight hunter, plenty of movement and jump from the TB, plus an amenable temperament and plenty of good bone

from the Vanner. If you cross such an animal with a TB again you end up with Eventers

and all round Sports Horses which are becoming increasingly popular.

The Coloured / Paint / Piebald or Skewbald – whatever you choose to call them, have

deservedly gained a new recognition for their terrific action, strength, and athletic ability. They are now a very popular and sought after breed here in Ireland, Britain, Continental Europe and Scandinavia.

The Welsh Pony & Cob Studbook of Ireland

WPCS

The Welsh Pony & Cob Studbook of Ireland is a daughter studbook of the breeding book of origin, ‘The Welsh Pony and Cob Society’ located in Bronaeron, Felinfach, Lampeter, SA48 8AG Wales.

https://wpcs.uk.com/

and it follows the principals established by the breeding book of origin.

Geographical areas covered: Republic of Ireland.

*Click here to request a DNA Kit (online order form)*

Definition:

Welsh Ponies and Cobs derived from a hardy native pony used essentially to carry the Welsh Shepherds up the hills to tend their sheep. The breed has been defined and developed since then. However, the characteristic and traits which originate from these ponies are evident in all sections and they are;

“An attractive head well set on, in good proportions showing a bold, intelligent eye set in a broad forehead, the lower head is fine with well-defined nostrils. The neck is elegant and long and can have a defined crest particularly in a stallion, with a good length of rein. The shoulders are notably well laid back with a defined wither. The ribs are well sprung with good depth of girth. The quarters are strong with a well set on tail that is characteristically carried well and, in some cases, gaily. They are generally of solid colour and show elevation and agility in their action. They are highly trainable in any discipline and are suitable for children and adults for Riding, Driving, Showjumping, Dressage and Eventing.”

ORIGIN OF THE WELSH PONY

The Welsh Pony is believed to be descended from the Celtic Pony and existed in the mountains of Wales for well over a thousand years enduring great hardship. As a result of this hardship, this breed has developed a hardiness of constitution and an intelligence which has made them one of the finest foundations for horse breeding in the world. Today, the Welsh mountain pony is acknowledged to be the world’s most beautiful pony.

For many generations the Welsh Section B was the means of transport for shepherds and hill farmers. With the increased popularity of children’s riding ponies, around 1930, this breed has developed along these lines whilst retaining adequate bone and substance, hardiness and constitution, combined with the usual kind temperament which is such an outstanding characteristic of the Welsh breed.

From references in early Welsh literature, it is apparent that the Welsh Cob was well established as a breed by the 15th century. The Welsh Cob is the ideal family horse as he is strong enough to carry an adult and quiet enough for kids to ride. Courage, intelligence and jumping ability make them ideal hunters for rough or hilly country. They also readily take the harness and have success in international driving competitions.

INTERESTING FACTS

The first written references to Welsh Ponies and Welsh Cobs appeared in the laws of Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), ruler of Deheubarth written in the year 930. As a result of these laws, Wales was the only nation in Europe to have a National Literature (as distinct from Latin) and this literature mentions three types of horse and ponies in Wales:

The Palfrey – i.e. the riding pony

The Rowney or Sumpter – the pack horse

The Equus Operarius or working horse – the light able bodied working horse that pulled the sledge or small gambo i.e. Cob rather than Shire horse

All evidence that is available shows that the Welsh Mountain Pony has existed, in all fundamental respects, very much as we know it now since prehistoric times. For hundreds of years, they ran wild throughout the country and were a nuisance to all farmers.

King Henry VIII (1509 – 1547) considered that only animals that were capable of going to war were worth keeping and he ordered the destruction of all stallions under 15hh and mares under 13hh. Fortunately, some animals escaped slaughter by escaping into the hills of Wales and like many other breeds survived because of their intelligence and inherent virtues, a trait that has been passed on when used as foundation stock for breeding children’s ponies.

Welsh Ponies and Welsh Cobs have `Arab’ like features and it is said this comes from Romans which were abandoned in the United Kingdom in 410 AD.

There has been some discreet infusion of Thoroughbred, Eastern and Hackney blood in the breed.

Around 1700AD, farmers began to realise that the Welsh Pony and Welsh Cob could actually be an asset if grazed alongside sheep and cattle and a market began to grow. The demand began to increase and hundreds started changing hands at big autumn fairs. Around this time, people began to take an interest in breeding and stallions were more carefully selected.

In 1901, a number of farmers, landowners and enthusiasts formed the Welsh Pony and Cob Society and the first volume of the Welsh Pony studbook was printed. Members amounted to 200 and very soon the Welsh Pony became world famous. By 1920 100-200 ponies were being exported as far afield as Australia.

Welsh Ponies were only accepted into the studbook in in the early 1900’s if they could trot 35 miles uphill from Cardiff to Dowlais without stopping!! Hence the Welsh Pony is known for endurance.

Today there are roughly around 8,000 members of the Welsh Pony and Cob Society.

WELSH PONY SECT A

Not EXCEEDING 121.9 (CMS) 12HH

Section A of the studbook

Characteristics:

General Character – Hardy, spirited and pony like.

Colour – Any colour except piebald and skewbald.

Head – Small, clean cut, well set on and tapering to the muzzle.

Eyes – Bold.

Ears – Well placed, small and pointed, well up on the head proportionally close.

Nostrils – Prominent and open.

Neck – lengthy, well carried and moderately lean in the case of mares, but inclined to be cresty in the case of mature stallions.

Shoulders – Long and sloping well back. Withers moderately fine but not “knifey”. The humorous is upright so that the foreleg is not set in under the body.

Forelegs – Set square and true, and not tied in at the elbows. Long, strong forearm, well developed knee, short flat bone below the knee, pasterns of proportionate slope and length. Hooves dense.

Back and Loins – Muscular, strong and well coupled.

Girth – Nice deep girth.

Ribs – Well sprung.

Hindquarters – Lengthy and fine. Not ragged or goose rumped. Tail well set on and carried gaily.

Hind Legs – Hocks to be large, flat and clean with points prominent to turn neither inwards or outwards. The Hind legs not too bent. The hock not to be set behind a line from the point of the quarter to the fetlock joint. Pasterns of proportionate slope and length.

Action – Quick, free and straight from the shoulder. Knees and hocks well flexed with straight and powerful leverage and well under the body.

How they are known – very clever and kind. They are perfect first ponies and excel in lead rein, pony club, jumping and gymkhana.

SECTION B – THE WELSH PONY

Not exceeding 137.2 cm (13.2hh)

Section B of the Studbook

Characteristics:

General – The Section B pony is generally the same looks wise as the Section A however a Section B is generally described as a riding pony that has quality, riding action, adequate bone and subsistence, hardiness and constitution and above all a pony character.

How they are known – they have a more animated trot than the Section A and a very useful all round ponies.

SECTION C – THE WELSH PONY OF COB TYPE Characteristics:

Not exceeding 137.2 (13.2hh)

Section C of the Studbook

The Welsh Pony of Cob Type – Section C is the stronger counterpart of the Welsh Pony the only difference been they have Cob blood

Their truth worth as a dual-purpose animal has been fully realised in recent years, therefore their numbers have increase accordingly

Active, sure footed and hardy they are ideal as kids ponies but also double up as adults’ ponies

Like all the Welsh Breeds they are natural jumpers and they also excel in harness. There are very few disciplines that they cannot be used in.

SECTION D – THE WELSH COBCharacteristics:

The height should exceed 137cms (13.2hh) and there is no upper limit.

Section D of the Studbook.

Aptly described as the “best ride and drive animal in the world”, the Welsh Cob has evolved throughout many centuries for his courage, tractability and powers of endurance. The Welsh Cob is a good hunter and a most competent performer in all sports. In recent years they have had great success in the driving world. Their abilities in all sports are fully rejoiced throughout the world.

Character – is the embodiment of strength, hardiness and agility.

Head – shows great quality and pony character.

Eyes – bold prominent eyes, a broad forehead and neat well-set ears.

Body – deep on strong limbs with “good hard-wearing joints and an abundance of flat bone.

Action – must be straight, free and forceful, the knees must be bent and then the whole foreleg extended from the shoulders as far possible in all paces, with the hocks well flexed, producing powerful leverage.

THE WELSH PART BRED REGISTER

All animals entered in the four sections of the Studbook mentioned above can vary in size and substance but all will show a common resemblance to their ancestor, The Welsh Mountain Pony.

The best inherit the strong constitution, good bone, courage, intelligence and equable temperament that has led to worldwide renown.

This has led to there been the need for a Welsh-Part Bred register for horses, ponies and cobs. To be entered into this register the animals breeding must show not less than 12.5% Welsh blood – this would generally mean the animal has one parent of Welsh origin.

EXCITING NEWS

The Welsh Pony and Cob Society was delighted to announce its Breeding Program which has been approved by DAFM.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN?

This means that all Pure and Partbred Welsh Ponies and Cobs can now be registered in Ireland, as EU Legislation dictates.

HOW AND WHERE CAN THIS HAPPEN?

With consent from the WPCS (Wales), Leisure Horse Ireland has been approved as a ‘daughter society’ of the WPCS and is the keeper of the studbook.

PASSPORTS

The Passports will be unique to the Welsh Pony & Cob Society of Ireland and will be the official document for all Welsh Pony & Cobs that are bred within the twenty six counties.

The Irish Clydesdale Horse Studbook

ICHS

The Irish Clydesdale Horse Studbook is the daughter studbook of the breeding book of origin, ‘The Clydesdale Horse Society’ which is located at 7 Turretbank Place, Crieff, PH7 4LS, Scotland,

https://clydesdalehorsesociety.com

and it follows the principals established by the breeding book of origin

Geographical areas covered: Republic of Ireland and selected EU Countries

*Click here to request a DNA Kit (online order form)*

Essential Traits:

The Clydesdale Horse is a draught horse, typically of 16 to 18 hands high and weighing on average 1,600 – 1,800 pounds. Clydesdale horses are very docile, gentle, intelligent and have a ‘majestic’ outlook, with an average lifespan of 20-25 years. They are built for power and their large feet area have spring like capabilities which act like shock absorbers under the pressure of heavy loads. These feet, together with sound, well-built limbs and a powerful trunk, provide the power of the horse which was bred principally for moving large loads quickly and efficiently.

The Origin of the Clydesdale Horse

The Clydesdale is a breed of heavy draft horse developed in and deriving its name from the district in Scotland where it was founded. Its type was evolved by the farmers of Lanarkshire, through which the River Clyde flows. The old name for Lanarkshire is Clydesdale.

The type was bred to meet not only the agricultural needs of these farmers, but also the demands of commerce for the coal fields of Lanarkshire and for all the types of heavy haulage on the streets of Glasgow. The breed soon acquired more than a local reputation and, in time, the breed spread throughout the whole of Scotland and northern England.

The district system of hiring stallions was an early feature of Scottish agriculture and did much to standardize and fix the type of the breed. The records of these hiring societies go back in some cases to 1837. The Clydesdale Horse Society was formed in 1877 and has been an active force in promoting the breed not only in Great Britain but also throughout the world. The Clydesdale alone, of the British breeds of heavy draft, has enjoyed a steady export trade to all parts of the world. The most active trade has been to commonwealth countries and the United States of America. Today, the Clydesdale is virtually the only draft breed in its native Scotland and New Zealand. It holds a commanding lead in Australia and is popular, though not the numerical leader, in Canada and the United States of America.

Characteristics

The Clydesdale is a very active horse, not bred for action, like the Hackney, but he must have action. A Clydesdale judge uses the word “action” with a difference. A Hackney judge using the word means high-stepping movement; a Clydesdale judge means high lifting of the feet, not scuffling along, but the foot at every step must be lifted clean off the ground, and the inside of every shoe be made plain to the man standing behind. Action for the Clydesdale judge also means “close” movement. The forelegs must be planted well under the shoulders – not on the outside like the legs of a bulldog and the legs must be plumb and, so to speak, hang straight from the shoulder to the fetlock joint. There must be no openness at the knees, and no inclination to knock the knees together. In like manner, the hind legs must be planted closely together with the points of the hocks turned inwards rather than outwards; the thighs must come well down to the hocks and the shanks from the hock joint to the fetlock joint must be plumb and straight. “Sickle” hocks are a very bad fault, as they lead to loss of leverage.

A Clydesdale judge begins to estimate the merits of a horse by examining his feet. These must be open and round, not thin and flat. The hoof heads must be wide and springy, with no suspicion of hardness that may lead to the formation of sidebone or ringbone. The pasterns must be long, and set out at an angle of 45 degrees from the hoof head to the fetlock joint. A pastern which is too long is very objectionable, but very seldom seen.

A Clydesdale should have a nice open forehead (broad between the eyes), a flat (neither Roman-nosed nor “dished”) profile, a wide muzzle, large nostrils, a bright, clear, intelligent eye, a big ear, and a well-arched long neck springing out of an oblique shoulder with high withers. His back should be short and his ribs well sprung from the backbone, like the hoops of a barrel. His quarters should be long, and his thighs well packed with muscle and sinew. He should have broad, clean, sharply developed hocks, and big knees, broad in front. He should have good flat bone. The impression created by a thoroughly well-built typical Clydesdale is that of strength and activity, with a minimum of superfluous tissue. The idea is not grossness and bulk, but quality and weight. He should have plenty of feather and be ‘silky’ to touch.

Colour

Clydesdales are usually bay in colour with a Sabino like pattern. Black, grey, and chestnut also occur. Most have white markings, including white on the face, feet, and legs and occasional body spotting (generally on the lower belly).

How time has influenced the Clydesdale

As with all breeds of livestock, the Clydesdale has gone through several changes of emphasis over the years to meet the demands of the times. In the 20’s and 30’s, the demand was for a more compact horse; of late, it has been for a taller, hitchier horse. Most of the horses range in size from 16.2 to 18 hands and weigh between 1600 and 1800 lbs. Some of the mature stallions and geldings are taller and will weigh up to 2200 lbs. With the changes in the size and type of horse wanted, the Clydesdale emphasis on underpinning has remained paramount.

For anyone desiring an active yet tractable, intelligent, stylish yet serviceable draft animal for work, show, or simple pleasure, the Clydesdale merits his or her most serious consideration.

Interesting Facts

- In 1958 under the directorship of Alan Harper a film called “The Good Servant” was released. This tracks the story of the Clydesdale from a foal all the way to becoming Champion at the Royal Highland Show.

- In the 1960’s & 1970’s the numbers had dwindled so much so that the Rare Breeds Survival Trust named the Clydesdale as “Vulnerable”, now today the Clydesdale is branded “At Risk” because of the increasing numbers which are bred.

- The official Clydesdale Horse Society was launched on the eve of the Glasgow Stallion Show February 1877.

- The very first official Clydesdale Studbook was launched the following year in 1878.

- After the formation of the Studbook, Clydesdales were being exported in their hundreds and during the period from 1884 to 1945 there were 20,183 export certificates issued for stallions, mares & fillies (they were mainly exported to the United States of America, South America, Russia, Italy and Austria).

- Presently there are 250 foals recorded each year.

Shire Horse Studbook of Ireland

SHSI

What are Shire Horses?

The Shire horse is a breed of British Draught horse.

Why is the Shire Horse called ‘Shire’?

The Shire horse gets his name from the “Shire” areas of rural England that are used traditionally for heavy hauling and war.

What two breeds makes the Shire Horse?

The Shire is a breed of Draught horse that originated in England in the 17th century. During the 16th century Dutch engineers brought Friesian horses when they came to England and these horses probably had the most significant influence on what became known as the Shire Breed.

Characteristics of the Shire Horse

- The Shire horse was always known for the amount of hair and feather on the legs. However today the hair is finer and silkier.

- They are a draught breed of horse known for their large size and regal appearance.

- Shire horses are known for their calm, easygoing and patient nature.

- They are docile and very hard-working animals due to their origins

- They are not known to have any behavioral issues

Breed Definition of a Shire Stallion – a good stallion should have strong character

- Color – Black, brown, bay or grey. A good stallion must not be splashed with white anywhere on the body.

- Height – 17hands or 17.2 at maturity.

- Head – Long and lean head not too big or small with long neck in proportion to the body. A large jaw bone should be avoided.

- Eyes – Large and well set. Wall eyes are not excepted.

- Nose – slightly roman nostrils thin and wide, lips together.

- Ears – Long, lean, sharp and sensitive.

- Throat – clean cut and lean.

- Shoulder – Deep and oblique, wide enough to support the collar.

- Neck – Long slightly arched, well set on to give to give the horse a commanding appearance.

- Girth – The girth varies from 6 ft to 8 ft in stallions.

- Loins – standing well up, denoting good constitution must not be flat.

- Fore-end – wide across the chest with legs well under the body and well enveloped in muscle or action is impeded.

- Hindquarters – long and sweeping, wide and full of muscle, well let down towards the thighs.

- Ribs – round, well sprung and not flat.

- Forelegs – should be as straight as possible down to the pastern.

- Hindlegs – Hocks should not be too far back in line with the hindquarter with ample width broadside and narrow in front. “Puffy” and “sickle” hocks should be avoided. The legs sinews should be clean cut and hard like fine cords to touch and clear of short cannon bone.

- Bone Measurement – Of flat bone 11 inches is ample.

- Feet – Deep, solid and wide with thick open walls. Coronets should be hard and sinewy with substance.

- Hair – Not too much, fine and silky.

Breed Definition of a Shire Mare – a mare should be quality and feminine and have a matronly appearance with plenty of room to carry a foal.

- Color – Black, brown, grey or roan.

- Height – 16 hands upwards.

- Head – Long and lean, neither too large or too small. Long neck in proportion to the body, of feminine appearance.

- Eyes – Large well set and docile in appearance. Wall eyes are acceptable except for animals in Grade A and B of the register.

- Neck – Long and slightly arched and not of masculine appearance.

- Girth – 5 ft to 7 ft according to size and age of animal.

- Back – strong and in some instances longer than a male.

- Legs – short with short cannons.

- Bone Measurement – 9 to 11inches of flat bone with clean sinews.

What was the Shire Horse was used for?

In the 14th and 15th century horses were used for transportation and pulling carts. By the 18th century with the change in technology especially on the farm the animal of choice was the horse. The Shire was perfect for this job due to their height and stature. During the second half of the 18th century the Shire was then used to pull carts, and barges. However, the railway system then meant that the need for horses to draw heavy loads was declining. However, in 1893 it was estimated that the brewer companies used around 3,000 horses many of which were shires for deliveries. Also, coal was delivered by horses many of which were shires. So, from 1920 onwards motorized transport was quickly replacing the need for horses to do these deliveries and the number of shires began to decline.

Shire horse numbers fell from well over a million to just a few thousand by the 1960’s and the breed was in serios trouble. A small group of very dedicated breeders came to the rescue and the Shire seen a resurgence in popularity as both a riding horse and also a working animal.

Uses of the Shire Horse today?

The Shire is used a lot today in the leisure horse industry pulling carts and gypsy caravans and canal barges for holiday makers. The Shire is now popular at all the big shows in the UK with special classes as riding horses (heavy horse classes). There is a Shire Horse Show which is held at Staffordshire Showgrounds in the UK in May every year. You will always find the Shire horse at ploughing matches both in Ireland and the UK.

The Irish Donkey Studbook

IDS

Irelands dedicated donkey studbook which allows registration with or without pedigree recorded.

Geographical areas covered: Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland & EU

Definition:

An Irish Donkey is small and compact.

Ears: Longer than a horse.

Hooves: Smaller and rounder than a horse.

Coat Colour: Coats vary in colour with grey, brown, and black, roan, piebald and skewbald accompanied by stripes, spots, ear markings, white muzzles, eye rings or white bellies.

Tails: Thin with a tasselled end.

Mane: Stiff and coarse, usually sticking straight up.

Size: The size of donkeys varies.

The standard female donkey reaches around 137 cm while the male reaches around 142 cm.

Donkey Origins

Donkeys were first domesticated from wild asses around 7,000 years ago in East Africa, perhaps helping humans adapt to more arid conditions. Donkeys then appear to have radiated out from East Africa, being traded northwest to Sudan and onwards into Egypt. Donkeys made a huge difference in humanity’s ability to transport goods over long distances by land, due to the animals’ endurance and ability to carry heavy burdens. Over the following 2,500 years, this new domesticated species spread throughout Europe and Asia, developing the lineages that are found today.

Between the 2nd and 5th Century, the Romans bred them for producing mules [by cross breeding them with horses] which played a key role in transporting military equipment and goods,” he says. “Though they were in Europe, they were bred and mixed with donkeys coming from western Africa.

Early research indicates that donkeys were used by the wealthy as a status symbol. In the past, donkeys were used for agricultural work in the Roman colonies in Northern and Western Europe. In Mediterranean countries, donkeys were also used for agricultural work and for work in the vineyards

Most donkeys have a darker, narrow, cross-like strip of hair that runs down their backs and shoulders. Christian tradition maintains that originally donkeys had unmarked hides. It is Christian belief that the dark cross on a donkey’s back only originated after Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. In Christian scripture, Jesus rode into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday on a donkey. After Christ died on Good Friday, it is maintained that all donkeys received the mark of a cross on their back as a reminder of the service that they did to Christ on Palm Sunday.

Donkeys were also used for medicinal purposes. For example, donkey’s milk was given to those suffering from tuberculosis and to premature babies. During the Middle Ages, the hairs from the cross on a donkey were worn in a chain around the neck to guard against toothache, fits and whooping cough.

Donkeys in Ireland

Donkeys are thought to have been brought into Britain by the Romans during the Roman invasion of the 1st century A.D. The earliest known documented reference to a donkey in Ireland is in 1642 when a reference was made to a donkey being seized in the capture of Maynooth castle.

It was not until the 19th century that the donkey rose to prominence in Ireland. During the Peninsular War (1808-1814), many donkeys were brought to Ireland by the British who were fighting against the French army. As Irish stallions were in high demand on the continent, the British army traded donkeys in

exchange for horses. After this time, the donkey appears much more frequently in Irish records.

In Ireland, donkeys were used by people for transportation purposes. As donkeys have the ability to carry and pull loads up to twice their body weight, donkeys were an invaluable asset to farmers. They were used for ploughing and working crops, collecting turf, transporting potatoes and seaweed, and for transporting other goods. In today’s society, while some donkeys are still used for work purposes,

most are pets.

Donkeys have been a far more constant companion of humans than their equine relatives, horses. Modern domestic horses, which were domesticated around 4,200 years ago, have had a huge impact on human history and research now reveals the impact of donkeys extends even further. The animal’s lasting utility sits somewhat in contrast to the amount of attention it has received compared to horses and dogs. While today donkeys are largely overlooked in many parts of the world, in some places, however, they are still as important as they ever were.